Picturing Spirituality: What Can Drawings Reveal about Spirituality?

Drawing from the data collected for the Fetzer Institute Study of Spirituality in the United States, I sought to focus on the visual data (drawings) generated during the focus group stage of the project. These 96 drawings and the focus group transcripts that accompany them represent a unique opportunity in the visual sociology of religion. As far as I can tell, no one has used this particular technique (i.e., drawing elicitation) to study spirituality.

What does spirituality look like? If you were handed a blank sheet of paper and colored pencils, what would you draw? And when asked to describe your picture, how would you explain your understanding of spirituality? As part of the Study of Spirituality in the United States, focus group participants produced drawings and definitions of spirituality. These materials were compared to an unrelated nationally representative study in which survey respondents were asked to write a definition of spirituality in a sentence or two. Did the task of drawing spirituality make a difference in how people responded?

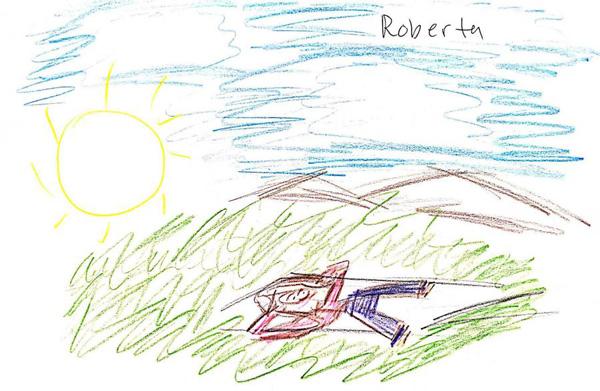

Interestingly, definitions of spirituality elicited through focus group participants’ drawings most frequently refer to the natural world and the self, as in the drawing below, whereas the words-only responses of the comparison study emphasized monotheistic deities (God, Allah, or Yahweh) and higher beings (higher power or supreme being). Participants who began their definitions by drawing spirituality oriented it toward emotional, existential, ethical, behavioral, and relational dimensions at higher rates than the comparison study’s respondents, whereas open-ended survey responses were more cognitive (emphasizing belief, faith, knowledge, or meaning). The drawing-based study helped illuminate aspects of spirituality that may not have been noticed otherwise.

“I guess I kind of interpreted it as being sort of at peace and being relaxed and able to reflect, so I had myself sort of lying in the field, and lying down, and my hands up behind my head, and I’m just kind of looking up hopefully with a sort of a contemplative look on my face. And it’s nice out. A little cloudy, but sunny. And that's kind of how I interpreted it. . . . Maybe contemplating, and I don’t know if I used it when I was describing, but also being more self-aware and able to reflect on things that are meaningful to me.” Roberta S., 64, Boston (Religious, Not Spiritual).

While the perspective these data offer on spirituality is important, equally important is the methodological contribution this study makes in the social-scientific study of religion. Simply put, whom one asks is as important as how one asks. By starting with a prompt to draw spirituality, Study of Spirituality in the United States focus group facilitators invited participants to go down pathways that a words-only survey response did not make available. To ask someone to visualize spiritual and religious phenomena through pictures is to invite a narrative. And this is a very different starting point from a words-only definition.

Roman R. Williams, Ph.D. is a visual sociologist who studies religion and spirituality in everyday life.